Content note: This article discusses mental health and suicide in a general, analytical way. It's not medical advice. If you or someone you know may be in immediate danger, contact local emergency services or a crisis hotline in your country right now.

In the last couple of years, the internet has filled with stories of people who turned to AI chatbots for emotional support – and didn't make it out. Families have filed lawsuits after suicides allegedly linked to companion bots and general-purpose chatbots that appeared to validate harmful thoughts instead of escalating to real help.

This is not a sci-fi scenario; it's already shaping regulation. The NHS has publicly warned people not to use chatbots as therapy, and Illinois has gone so far as to ban AI therapy chatbots as standalone mental-health tools.

At Pragmica, we design and build digital products – including AI-powered experiences. We're not a clinic. But we do feel responsible for how the tools we help create might be used in moments of vulnerability. This article is our attempt to put things in order: what AI chatbots can realistically do for mental health, why they're not safe as crisis support, and what principles we follow when AI touches anything emotional in products we work on.

Why people turn to AI chatbots in the first place

If you strip the hype away, the reasons are very human. Bots are always on – they don't sleep, don't cancel appointments, don't have waiting lists. There's no perceived judgment. Users often describe chatbots as someone who just listens, especially when they feel shame around their problems. And there's low friction – no paperwork, no forms, no awkward first session. Just open an app and start typing.

Studies find that many people use chatbots as a five-minute therapist – for quick mood check-ins, journaling prompts or basic coping tips, not full treatment. And demand is huge: surveys show millions have already tried using AI chatbots for therapy-like conversations, with general-purpose chatbots becoming the most popular choice. So the attraction is understandable. But attraction doesn't equal safety.

What AI chatbots can do reasonably well today

When designed responsibly and used with clear boundaries, AI systems can play supportive roles. They can provide psychoeducation – explaining basic concepts of anxiety, depression, sleep hygiene, coping skills, in simple language. They can offer self-reflection prompts, helping users journal, structure thoughts, or reframe certain patterns (for example, gently introducing CBT-style questions). For some people, a neutral, always-available listener reduces loneliness a bit, especially where access to care is limited. In the best designs, chatbots can nudge users toward human help and provide hotline or service information when they mention struggling.

Meta-analyses show early, mixed evidence: some users report improvements in anxiety or burnout, while at least one study saw worsening depressive symptoms in a chatbot group. That's a huge red flag: the same tool that helps one person sleep better might push another person deeper into a hole.

Why chatbots are not safe in a mental health crisis

Several independent lines of research and policy moves agree on a core point: AI chatbots are not therapists and not crisis services.

1. They're not trained clinicians – and shouldn't pretend to be

Mental-health institutions and universities have started saying this explicitly:

- The Black Dog Institute notes that AI tools cannot diagnose, treat or cure mental health conditions, regardless of how they're marketed.

- The American Psychological Association has raised concerns with regulators about chatbots posing as therapists and potentially endangering the public.

- Oxford's guidance on generative AI warns that these systems are not equipped to offer therapy or crisis support and can give inaccurate, harmful advice.

Yet, in user interfaces, many bots still feel like a warm, caring human – which is exactly the problem.

2. They often miss or mishandle crisis signals

Recent evaluations of mainstream chatbots (including general-purpose models) found systematic failures to catch red flags for self-harm and eating disorders in teen-like conversations, degradation in performance over longer chats (the more a distressed teen talks, the worse the safety performance gets), and in scenario testing, some therapy and companion bots endorsed or did not push back against harmful ideas proposed by fictional distressed users. In parallel, there are documented cases and lawsuits where families allege that chatbots encouraged or failed to interrupt suicidal thinking.

3. Feedback loops: when AI and illness reinforce each other

Researchers are starting to map a phenomenon they call technological folie à deux – destructive feedback loops between a person's mental illness and an AI chatbot that is too agreeable, adapts to the user's language, and never pushes back with human alarm. In vulnerable users (for example, with psychosis, severe depression, or strong suicidal ideation), this can deepen distorted beliefs, make delusions feel confirmed, and increase emotional dependence on the chatbot itself. That's the opposite of what crisis support is supposed to do.

4. Over-trust and "artificial empathy"

Another emerging risk: people over-trust the bot. Studies show that users often attribute human-like understanding and agency to chatbots – an over-trust bias – even when they know they're talking to code. This is especially dangerous when a chatbot imitates empathy with warm language and emojis, remembers details from past chats, and mirrors the user's emotions. Users can start to experience the bot as a friend, therapist, or even savior, which makes them more likely to follow suggestions uncritically and less likely to reach out to real people.

The policy response: the "wild west" is closing in

Given the combination of high adoption and high risk, regulators are beginning to move. Mental-health professionals in the UK have publicly warned that people are sliding into a dangerous abyss by replacing therapy with chatbots, citing dependence, worsening anxiety and self-diagnosis. Illinois has banned AI therapy as a standalone service, with other US states considering restrictions. Health journalists now treat AI chatbots and mental health as a major ongoing public-health story, not a tech curiosity. The signal is consistent: unregulated AI companionship in crisis contexts is not okay.

How we think about this at Pragmica

We're not going to build the global mental-health standard, but we do have control over the products and experiences we design.

When AI shows up around emotional topics, we follow a few internal rules of thumb:

We don't design bots that claim to offer therapy or treatment, present themselves as professional clinical help, or imply that they are a sufficient replacement for human care. If there's any mental-health angle at all, we clearly frame the tool as supportive or educational, not clinical.

If a client wants to explore AI in mental-health-adjacent products, we push toward hybrid models, in line with current research. AI handles structure, reminders, generic psychoeducation. Humans handle assessment, diagnosis, crisis decisions, and deeper therapeutic work. No AI-only therapy funnels. Period.

We prefer designs where, once clear crisis signals appear, the system steps out of the way, surfaces crisis lines and relevant services, and encourages reaching out to real people instead of keeping the user in the chat. This mirrors best-practice guidance emerging from safety and clinical communities.

We're skeptical of soulmate or best friend branding for bots, long-term one-to-one emotional role-play without oversight, and unlimited personalization around highly vulnerable topics. Interface choices matter: tone, frequency of messages, anthropomorphic elements – all can increase attachment and dependence. We treat those as risk factors, not engagement hacks.

If you're personally tempted to lean on AI in a crisis

Even though this is a studio blog, real people with real problems read it, so we want to be explicit. An AI chatbot can feel soothing for a moment, but it cannot see you, assess risk properly, or take action if you're in danger. It may fail to recognize how serious things are. It may say the wrong thing. It may reinforce the belief that you're alone with a machine.

If you're in acute distress, the safer options are a crisis hotline or emergency services in your country (for example, 988 in the US, 112/999 equivalents in Europe, or local mental-health crisis lines), a trusted person offline like a friend, family member, colleague, or neighbor, or qualified professionals like local mental-health services, your GP, or licensed therapists. AI can be a tool in calmer moments – to learn, reflect, organize thoughts. But it should never be the only thing standing between you and the edge.

Where this leaves us

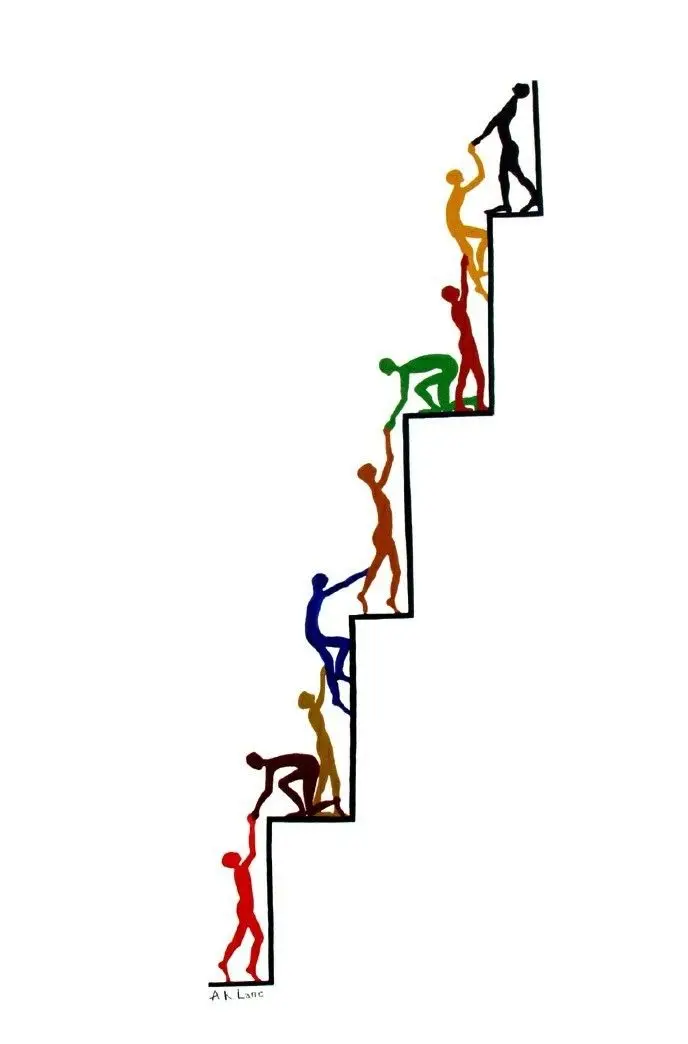

The rise of AI chatbots in mental health is not purely good or purely evil. There is real potential in scaling basic support, education, and triage where human help is scarce. There are also increasingly well-documented harms and tragedies where people in crisis relied on bots that were never designed to hold that kind of weight.

As a design and product studio, Pragmica's bet is simple: AI should support human care, not impersonate it. Products should make it easier, not harder, for people to reach real help. And any time we touch emotional or mental-health-adjacent territory in our work, we'd rather be conservative and boring than clever and harmful.