If, during every sprint review, a founder says to the dev team, "I just hope nothing breaks this time…" – it's usually not about bad developers. Very often it's a symptom of something deeper: the product is living without documentation.

In such projects, the client starts to feel dependent on one specific developer, afraid to change anything, afraid to change team members, and constantly worried that one small tweak will blow up half the system. Let's look at why this happens and how documentation fixes the root cause, not just the symptoms.

"I hope this time nothing breaks"

There are two common reasons why a client becomes hostage to the team. Either a specific specialist really holds unique knowledge that nobody else has, or there is no proper documentation, so all knowledge lives only in people's heads and in the code.

If you look at it from a classical project-management perspective, the obvious solution would be to analyze the current state of the project, review and adjust development processes, create or update missing documentation, train the team if needed, and align expectations and requirements with the client. Only after all this, if problems still remain, you can talk about changing people or teams.

In reality, what often gets sacrificed first is documentation. It feels like an overhead: "We don't have time for docs, we need features and release dates." The consequence is that the longer the product lives, the more fragile and unpredictable it becomes.

"Docs are useless"… or not?

At the very beginning, before the first releases, documentation really can feel like a luxury. Requirements are still changing, priorities jump every week, and the main pressure is to ship something that works. But as the product grows, a pattern appears: a change in one module breaks something unrelated, bug fixing takes longer than building new features, onboarding new engineers becomes painfully slow, and nobody is fully sure how a critical feature is supposed to behave. At this stage, lack of documentation becomes a bottleneck.

Let's walk through three very typical situations.

Situation 1. You need to change a component—but nobody remembers how it works

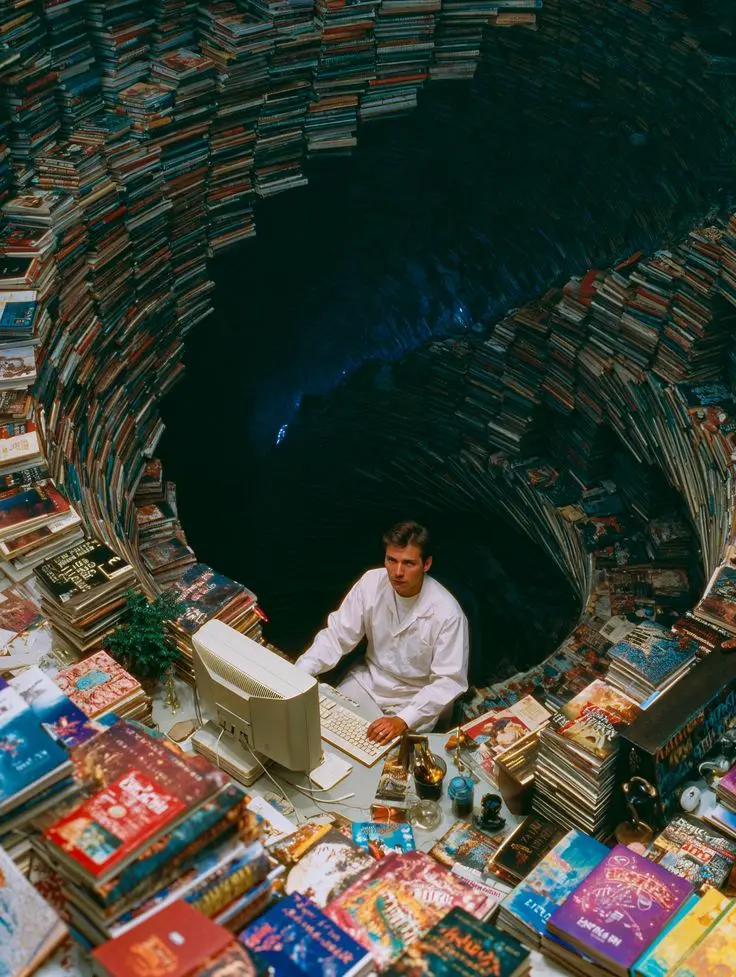

The team has already touched this component several times. It's been months; details are fuzzy. A developer sits down, digs through the source code and tries to reconstruct the original logic. Without any docs, this becomes archaeology, not engineering.

They make changes based on their own understanding, run smoke tests, and send it to the client. On the surface, everything seems fine. The client checks the happy path and approves the release. What nobody sees is how this component interacts with other parts of the system, what non-obvious edge cases exist, or what assumptions were made years ago but are no longer valid.

As a result, a bug appears somewhere else in the system. Nobody expected it. Nobody connected it with the original change. Users are the first to discover it. The key problem: without documentation, every change is a guess. Developers spend extra time deciphering code, and the probability of regressions grows with each release.

Situation 2. A user reports a bug—and fixing it becomes a quest

A user finds a problem and submits a ticket. The client forwards it to the team: "Fix this, please." Two branches of the story are possible.

Branch A: "The system is working as designed"

The developer inspects the code and sees that this bug is actually expected behavior, justified with an old comment in the code. But the user still isn't happy. So treating this as not our problem will hurt satisfaction and retention. The decision: accept this as an improvement request, change behavior in the future release, and make sure this new expected behavior is documented. Without proper documentation of current and desired behavior, the team falls back into Situation 1: again working from memory and interpretation.

Branch B: "This is a real bug"

The developer confirms it's an actual defect. They ask colleagues for context, schedule calls, and dig through the codebase trying to understand how the component is wired into the system. They fix what they see, but without a documented model of dependencies and constraints, it's hard to predict side effects. We end up again in a fragile situation where a fix in one module silently breaks another, testing is incomplete because nobody has a full picture, and the same class of bugs repeats.

The key problem: without documentation, even small incident response becomes expensive. Bug fixing is slower, riskier, and more dependent on a few hero engineers.

Situation 3. The user base grows—and optimization becomes dangerous

Good news: more users, more load, the product is gaining traction. The team decides to review performance, refactor architecture, and optimize bottlenecks for scale. But there's a catch: no up-to-date documentation of architecture, critical flows, or constraints.

The team changes the system, but testing is based on partial understanding. Nobody is fully sure which parts are critical, which dependencies are fragile, or what must never break in production. Some bugs slip into the release. Performance might improve in one place and degrade in another.

The key problem: without documentation, scaling becomes guesswork. You can't confidently evolve the product because nobody has a reliable map of how it works.

What founders and product owners need to understand

Without documentation – a single trusted source that describes what the product does, how specific features behave, and how components interact with each other – the entire project depends on individual memory and the code itself. And only developers truly read and understand the code.

That means the developer becomes the gatekeeper of knowledge, the client becomes dependent on that individual, and replacing the developer feels like starting from zero. A common mistake at this point is to think: "The problem is this developer. Let's hire a new one and things will get better."

In reality, a new engineer will spend months learning the same undocumented system, repeat old mistakes, and introduce new bugs while still discovering hidden logic. During that time, the product slows down, users get frustrated, and the business loses money and trust. The real problem isn't the person. It's the absence of any externalized knowledge about the product.

Documentation is not optional overhead. It's part of the product.

The longer a product lives, the more demanding it becomes toward documentation. At Pragmica, we treat documentation as a core part of the product, not as a side task that can be added later if we have time.

Good documentation stabilizes development speed over time, reduces dependency on specific individuals, lowers the risk of regression when making changes, helps onboard new team members faster, gives the client control and transparency, and makes scaling and refactoring less scary. When requirements and processes are not documented, you depend on a few people's memory, every vacation or team change becomes a risk, and small misunderstandings silently accumulate into expensive failures.

Documentation doesn't need to be massive or academic. But it must exist, be accessible, and be kept reasonably up to date.

What minimal documentation set is worth investing in?

The exact format depends on the project, but a healthy baseline usually includes business and product requirements (what problem does this product solve, for whom, what are the core use cases and success metrics), scope of work and feature specs (what exactly is included in the current phase, how should each feature behave, what are edge cases and constraints), system architecture overview (high-level diagrams showing services, modules, data flows, integrations), API and integration docs (contracts between services, external APIs, data formats, rate limits), and change logs or release notes (what changed, why it changed, and what might be impacted).

Even a lean, structured version of these documents dramatically lowers chaos.

Conclusion: documentation is priceless, not pointless

On a spreadsheet, documentation may look like an extra cost. In the real world, it's the thing that protects all your other investments: development budget, marketing spend, brand reputation, user trust.

Without documentation, you can pour money into building features, launching campaigns, and growing user numbers – and still end up stuck. Shipping is slow and risky, bugs keep returning, every change feels like Russian roulette, and the client feels they've lost control over their own product.

With documentation, you buy back control. You can change teams without losing knowledge, scale and refactor with a clear map, and align business, product, and engineering around the same understanding.

If you recognize your current project in the situations described above, the best time to start documenting it was yesterday. The second best time is now.

At Pragmica, when we join or build a product, we don't separate design and development from documentation – they grow together. That's how we keep complex systems understandable, maintainable, and safe to evolve.